No sooner was Tim Walz announced as Kamala Harris’s running mate than did his opponents on the right start amplifying criticisms of his military record. Based on slight evidence, he has been accused of retiring to avoid deploying to a combat zone; portraying his rank as higher than it is; and claiming he was in combat when he was not. Commentators quickly compared these attacks to the “swift boat” criticisms of John Kerry’s military record when he ran for President against George W. Bush.

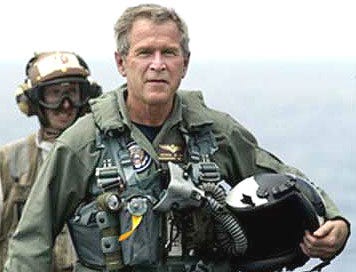

But let’s not forget that liberals have delighted in pointing out Trump’s lack of military experience and, most especially, his more than slightly questionable disqualification from the Vietnam War draft. Bush’s military record was also the subject of sustained criticism from liberals. Indeed, Kerry tried to situate himself as the candidate with the real military background.

These attacks may seem like ordinary political gamesmanship. But the way we fixate on political candidate’s military records reveals a lot about how gender operates in our political culture. To attack a male candidate’s military record is to indirectly attack his masculinity and, in turn, his civic membership.

Consider how much weight we put on military service as a credential for public office. Having a military record is a highly important resume item for any politician. While the percentage of veterans in public office has declined since its highpoint in the 1970s, they are still disproportionately represented. There is strong incentive for politicians to exaggerate their military experience, especially by overstating their proximity to combat. As the recent news about Wes Moore and Tim Sheehy remind us, the temptation to overstate or lie is strong.

At the same time, the military records of politicians and other public figures face unusual examination. We do not peruse their other professional activities to the same extent or in the same way. Of course, what our political leaders do in all their careers is politically relevant and professional misdeeds should haunt a candidate for public office. But the standards we apply to a politician’s civilian careers are not the same as the standards applied to their military records. For instance, Walz’s decision to retire from the National Guard occurred along with a decision to retire as a public-school teacher. While he has been called a traitor for retiring from the National Guard, it would be hard to imagine anyone levelling similar accusations for leaving his students and school.

And we should denounce a politician’s deliberate attempts to mislead the public about their service record. But here again there is a civil-military double standard. With military service, the slightest inaccuracies are seen as serious moral failings. Politicians do not need to be nearly as careful talking about their other professional activities as they do about their military ones.

Why do we simultaneously value and scrutinize the military experiences of political candidates in these unique ways? The answer is that military service has an unusual association with political membership. We treat the military as a civic proving ground—success in it demonstrates or redeems one’s civil standing.

Consider how oppressed groups have seen military service as an important step toward equality. Frederick Douglass, for instance, argued passionately for the right of Blacks to enlist and be treated equally within the ranks of the Union Army during the Civil War. Among other reasons, Douglass thought allowing blacks in the military would dramatically improve their political standing. As he wrote, “To fight for the Government in this tremendous war is…to fight for nationality and for a place with all other classes of our fellow citizens.”

Conversely, consider how the military achievements of oppressed groups have been systematically minimized and dismissed. Chad Williams’s recent book, The Wounded World, vividly describes W. E. B. Dubois’s frustrating struggle to get the achievements of Blacks in World War One acknowledged. And Sarah Percy’s recent book, Forgotten Warriors, comprehensively surveys the systematic denial of the battlefield contributions of women. The enemies of equality have feared military inclusivity for the same reasons that supporters of equality have sought it.

Consider too the practice, once common, of offering convicted felons the option of enlistment as opposed to incarceration as criminal punishment. Or consider the treatment of military service as a unique path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants. These practices are based on the idea that military service redeems or demonstrates a person’s civic membership.

Why do we so frequently think of the military as a civic acid test?

It is tempting to answer this question by pointing to the danger of military service. But lots of labor is dangerous yet we do not elevate those laborers politically. Meat packers do very dangerous work, but we do not view them as fuller members of political society as a result.

It is also tempting to answer this question by pointing to the contribution to the national interest involved in military service. But, again, lots of labor contributes to urgent national goods yet we do not treat those laborers as so politically special. Nurses, teachers, even mothers contribute vital goods to our nation, but their civil standing is not thereby improved, at least not nearly to the same extent as service members.

The best explanation of our thinking of the military as a crucible of civic belonging is our association of political membership with manhood and our association of manhood with military service.

Feminists have long pointed out how we have conceived of political society as a community of men who are sovereign over their wives. In most modern political theories women were explicitly left out of the social contract because of their “natural” subordination to men in domestic life. When the classic political theorists spoke of the rights of man, they usually meant that literally: man, and not woman. This vision of things puts only men in the position of full citizens.

But this is not a complete picture of how gender situates men in political society. At the same time as it includes them in the political community, it also saddles men with the “natural” duties of masculinity. These duties are not just about the nefarious patriarchal rule of households. Crucially, these duties include the obligation to fight and die in war for the commonwealth. In this vision, men are naturally free and equal and they are bound to go to war when called upon.

This is evident in many of the canonical political theories of the modern era. To cite just one example, Thomas Hobbes famously describes political society as a contract between men for their self-preservation. Less famously, to explain how these men can be obligated to risk their lives in war on behalf of the sovereign, Hobbes clearly appeals to the natural goodness of men’s (and not women’s) willingness to fight in war. Men who are fearful of battle have “feminine courage,” he says, and are failed men. Women, however, are naturally disinclined to engage in war and are therefore excused from service. So, underpinning Hobbes social contract is a gender theory that directly connects manhood with willingness to engage in war. Similar, though sometimes less explicit, appeals to masculinity can be found in Grotius, Pufendorf, Locke, and Vattel.

This view of masculinity is still with us. There remains an intimate connection between masculinity and violence, especially martial violence. Many scholars have concluded that the most direct way manhood is affirmed across cultures is through effective and fearless engagement in battle. A good man is, most immediately, a man who masters the arts of violence and employs them even when doing so puts his life in danger. Self-sacrificial contests of violence generally, but in warfare particularly, are where real men prove themselves. Failure to engage in these contests effectively, either by being defeated or, worse, by exhibiting an unwillingness to participate, undermines manhood.

These are the men we have imagined our political society as built for. The “citizen” is, in part, a military man. This is why we continue to think of the military as a civic proving ground.

For these reasons, the focus on Tim Walz’s military record is about much more than his resume. Questioning a man’s military record is indirectly questioning his manhood and his civic belonging. While today there is much more appreciation of the negative impact norms of masculinity can have on all genders, the fixation on the military records of our political leaders reveals we still have a lot of work to do.